Riley Carraher’s smile was almost as bright as the sunshine over AU Health on a recent September afternoon, as she sat on a campus bench and fondly recalled childhood days spent with her grandfather, packing DAISY Awards into cardboard shipping boxes to be sent off to local hospitals.

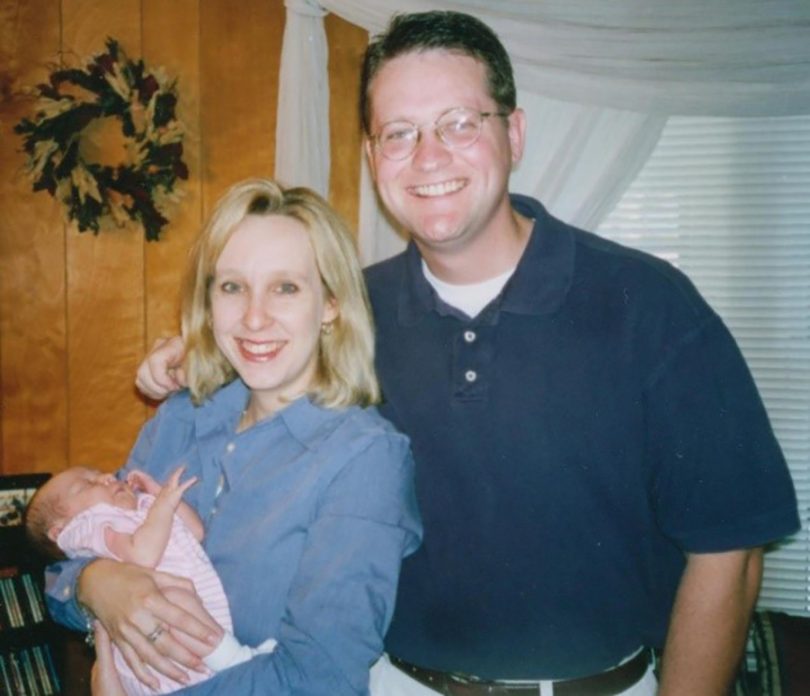

The 23-year-old Occupational Therapy student never knew her father, Patrick Barnes – he died when she was 3 months old – but his legacy is all around her, even in Augusta, Ga., 3,000 miles away from where she was born and where Barnes died.

Riley Carraher, sixth from left, attended the Daisy Award presentation for AU Health’s Daniel Ciccio in August.

At 33, he had been diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), an autoimmune disease. The care he received from the nursing staff first at Baptist St. Anthony’s Hospital in Amarillo, TX, and later at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle so impressed his wife, Tena, and parents, Bonnie and Mark Barnes, that they created the DAISY Foundation and the DAISY Award to honor nursing staff in his memory. (DAISY stands for Diseases Attacking the Immune System.)

The organization has grown from a small, grassroots, local effort to an international affair. Last year, Carraher attended a DAISY Award banquet and visited hospitals in Dubai. Similar celebrations have been held in Asia, Taiwan and the United Kingdom, in addition to over 5,000 hospitals across the United States.

To date, nearly 100 nurses from AU Health have been recognized with a DAISY Award.

Carraher said her grandparents and mom are the kind of people who always try to find the good in any bad situation.

“The one thing they found that was really exceptional (through Patrick’s illness) was the nurses,” she said. “Throughout all the bad times they were having and the long process, the nurses were always there. They gave comfort and delivered superior care. My family felt like my dad was being very well taken care of, so they decided to say thank you to his nurses in a very public way.”

The award itself that is presented to each honoree includes a Shona Sculpture from Zimbabwe that the foundation refers to as the Healer’s Touch. The Barneses felt the stone sculpture represented the relationship between nurses and patients. The sculptures are created by artisans in the Shona region of Zimbabwe, and the foundation’s purchase of them provides a steady stream of economic support for these artisans and their families.

“It’s my favorite part because it symbolizes the nurse and the patient relationship,” Carraher said. “It looks like two people sort of hugging each other.”

DAISY Award honorees not only receive the sculpture, but they also receive a certificate, pin, banner to hang in their unit and cinnamon rolls. Each hospital develops their own ceremony for additional recognition.

Even the cinnamon rolls have a special meaning, Carraher said.

“So my dad was really sick and didn’t have an appetite because of the medication. So he was eating absolutely nothing. One day my grandpa brought in Cinnabon cinnamon rolls and my dad was like ‘Oh, that smells so good! Can I have a bite?’ And he ate the whole thing,” she said, laughing.

Cinnamon rolls are now served at every DAISY Award celebration.

Riley Carraher, second from right, presents a Daisy Award with her grandparents, Mark and Bonnie Barnes.

The selflessness of the nurses she’s encountered over the years left a lasting impression on Carraher personally and guided her career choices. After her father died when she was 3 months old, she moved with her mother to Peachtree City, Ga., to be closer to Tena’s parents. Tena has worked with the DAISY Foundation from there and is now DAISY’s Vice President of Marketing and Communications , while the Barnes stayed in California, recently relocating to the Seattle area. (Sister-in-law Melissa Barnes is the Vice President of Operations.)

Riley Carraher grew up in Atlanta and graduated from the University of Georgia with a bachelors in bioengineering.

Today, Carraher is in her first year at Augusta University earning her Master of Science in Occupational Therapy and is looking forward to spending her career helping people. She credits growing up with DAISY with her decision.

“I don’t think I ever would have learned about OT or had so much of a passion to work in healthcare if it wasn’t for being surrounded by it all the time,” she said. “I’m not a nurse but it’s a different side of it, still getting to be in hospitals and seeing how that whole process works from an early age.”