It is the kind of story that makes headlines: A seemingly healthy child goes into sudden cardiac arrest while playing a game of tag with friends. The culprit: An undiagnosed heart defect.

These stories make headlines because the events are so rare, and oftentimes these children show no symptoms and go undiagnosed. Fifteen-year-old Natalie Claire Peppenger went to visit her family doctor for a routine sports physical when the doctor noticed an unusual heart rhythm.

The doctor referred the family to the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, where Natalie Claire was diagnosed with PVCs (premature ventricular contractions). Out of an abundance of caution, an echocardiogram was performed. What was found was more concerning: an abnormal coronary artery origin.

“If you have ever seen or read about an athlete who died in the middle of a game or had a serious cardiac event — this is what we were dealing with,” said Anna Peppenger, Natalie Claire’s mother and a pediatric float pool nurse at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. “Most individuals are not aware there is a problem until it’s too late. This is what makes our story so unique. It was found on a routine checkup.”

Dr. Kenneth Murdison, a pediatric cardiologist, diagnosed Natalie Claire and said this anomaly is rare. In fact, he personally recalls diagnosing only four similar cases in his 18 years at Children’s.

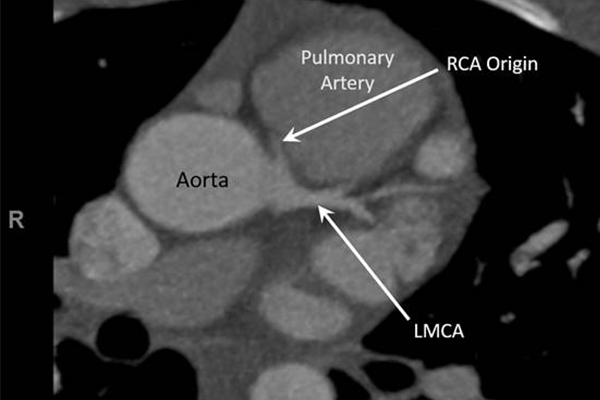

“In our practice, we would probably see something similar to this maybe once every one to two years,” he said. “Normally the coronary arteries branch off of the aorta, just above the aortic valve. You have two main coronary arteries, one that supplies the left side of the heart and one that supplies the right side of the heart. Natalie’s abnormality was that her right coronary artery didn’t connect to the correct area of the aortic valve apparatus. It actually took an abnormal course in front of the valve and traveled through the wall of the vessel to originate next to the left coronary artery origin.”

As a nurse, Anna Peppenger was used to hearing all sorts of diagnoses, but not when it involved her own daughter.

“When you’ve got a medical background, and you’ve got a child who faces something like this, you know, you become a parent,” she said. “And that’s what I kept telling all the doctors and the nurses who I obviously know very well. I told them to just treat me as a mom, this is my child. I’m obviously very scared and concerned, but the severity of what’s going on and what we had to do was bypass surgery — we had to stop the heart and restart it. But it was also comforting to know who I was involved with.”

Natalie Claire had open-heart surgery in October 2020. Along with Murdison’s involvement, Dr. James St. Louis, the cardiac surgeon and chief of pediatric and congenital heart surgery, performed the operation.

The operation was a success, much to the relief of her family.

“I walked into the Pediatric ICU to come see her for the first time,” Anna Peppenger said. “We’re in this corner room that I’ve been in so many times as a nurse taking care of patients, and, all of a sudden, there’s my kid’s name. That’s what was really surreal, and to see all the equipment and [IV] bags with her name on it.”

Within three weeks, Natalie Claire was healing and feeling better. She hopes to return to playing volleyball at school next year, something she hasn’t been able to do for a year.

Anna Peppenger had a new perspective when she returned to work, as well. “You just really feel a sense of connection with the people who are working with you and having to trust them. It gave me a new appreciation of being a parent on the other side of things for sure.”

Now 16, Natalie Claire has a scar from her surgery but she is happy, healthy and enjoying being active!

“To be honest, I don’t really remember a whole lot. I was very happy with the way I was treated and everyone was very, very, very kind.”